Writing With a Broken Tusk

Writing With a Broken Tusk began in 2006 as a blog about overlapping geographies, personal and real-world, and writing books for children. The blog name refers to the mythical pact made between the poet Vyaasa and the Hindu elephant headed god Ganesha who was his scribe during the composition of the Mahabharata. It also refers to my second published book, edited by the generous and brilliant Diantha Thorpe of Linnet Books/The Shoe String Press, published in 1996, acquired and republished by August House and still miraculously in print.

Since March, writer and former student Jen Breach has helped me manage guest posts and Process Talk pieces on this blog. They have lined up and conducted author/illustrator interviews and invited and coordinated guest posts. That support has helped me get through weeks when I’ve been in edit-copyedit-proofing mode, and it’s also introduced me to writers and books I might not have found otherwise. Our overlapping interests have led to posts for which I might not have had the time or attention-span. It’s the beauty of shared circles—Venn diagrams, anyone?

Guest Post: Varsha Bajaj on Kavi, 2023 American Girl

Picture book and middle grade novel writer Varsha Bajaj’s poignant story about a girl pursuing water justice in Mumbai has been described as “a powerhouse of a middle grade book,” “a valiant call for justice.”

Now Varsha takes on quite another kind of writing project—the companion books to the 2023 American Girl doll, our own South Asian American Girls Doll—Kavi. Varsha writes here about how this project came to be.

Reading the Future in Situ

Not for the first time, I’m wondering if it was a good idea to read Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future while visiting India. In the book, the temperature hits 42° C in Delhi (that’s over 107° F). The protagonist, working for an NGO, persuades the locals to go dip in a lake, which turns out to be hellishly warm and dreadfully polluted.

We Have Been Taught…

This July 4th seems as good a day as any other to reflect upon the nature of history—whose it is and who’s depicted in it? Who tells the story and why?

Process Talk: Martine Leavitt on Buffalo Flats

When I finished reading Buffalo Flats by Martine Leavitt, I wanted to go back to the beginning and read it all over again. I had a visceral memory of the spirit of her protagonist, Rebecca, from Martine’s readings of drafts at VCFA residencies. I found that spirit in these pages, carrying its sparkle all the way through. It made me feel as if I were encountering an old friend. Here’s my conversation with Martine about this beautifully crafted book.

Narrative Momentum in Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan

Thank you to Sarah Ellis for recommending Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan. It’s a short novella set in Ireland in the days of the Magdalene laundries, but that is not what it is about. Rather, it is the story of a man who deals in coal, a man with an ordinary life, a life that has turned out well, a man with no more than ordinary worries—but one who has nonetheless carried a hole in his heart since his childhood. See Keegan’s interview with another Claire, Claire Armitstead, in The Guardian, in which she expresses a refusal to condemn any of her characters, no matter how terrible their actions might seem.

What Makes Us Who We Are? The Ugly Little Boy by Isaac Asimov

Isaac Asimov’s short story, “The Ugly Little Boy,” was one of his own favorites, a tale of a nurse and the little Neanderthal child she’s been hired to care for. In Asimov’s words:

…I have received letters from people who say that they cried when they read the last part of the story, and I always answer and say well I'm glad they did because I cried when I wrote it and in fact I cried when I just read it, so I guess it means something to me.

I read “The Ugly Little Boy” not in its first appearance in Galaxy magazine under title “Lastborn” but in the Nine Tomorrows collection. The Neanderthal child has been brought via time travel to a specially constructed lab to be studied.

“Most Illustrious Lord…” Da Vinci in the Self-Promotion Department

I don’t like promotion. It doesn’t come easily to me and yet, it’s a necessary part of the work a writer has to do..

For some years, on my book shelf, I’ve had a slender volume titled Lives of Leonardo da Vinci. It’s a compilation of contemporary biographies, letters and eyewitness accounts.

Board Books for Toddlers—and Grownups Too

I had the great and joyful privilege of spending ten days earlier this year with my little granddaughter, who was not yet two at the time. She has figured out how a book works.

You open it up. You turn the pages. You talk to the book. Sometimes you prop it up and look over the edge, so you can keep a sharp eye on what might be going on beyond its covers. Maybe that’s just in case something important gets away. When you are all done, turning and talking in both directions, you close the book and hand it to a grownup and demand that this person read it to you. Ideally several times over.

One hot favorite was moi moi: Look at Me! by Jun Ichihara, edited by Kazuo Hiraki.

Personal Geographies

Place is at the heart of who we are. We hold it close. We mourn its loss. Time makes this a constant, because the place that made you keeps changing, long after you have left it. In a very literal way, maybe it never existed except in your fleeting experience of it.

Dorthe Nors writes of the grip we keep on a place, and how it both holds us and eludes us, in her book of essays on the North Sea coast in her native Denmark, A Line in the World.

Youth vs. gov in 2023

Like fiction, the law is also created and upheld through narrative. Whose narratives of reality are in contest? Whose will prevail? Who’s making those judgments and why? The answers to these questions will determine the real-life futures of young people. That is why I’ve been so intrigued by the young plaintiffs taking governments to court wherever they can, using the laws that exist, all with a singular purpose—to force governments to take action to limit the damaging effects of fossil fuel emissions.

South Asian Footsteps in Berkeley, CA

Footsteps. We leave them behind us, and we’re often unaware who has walked before us on the ground we tread.

In Berkeley, California, Barnali Ghosh and Anirvan Chatterjee are long-time San Francisco Bay Area activists and community-based historians who run a walking tour to fill this gap in knowing. You can find more on their Berkeley South Asian Radical History Walking Tour on a recent episode of the Atlas Obscura podcast.

The tour is based on oral history and archival research as well as the organizers’ active engagement with historical research in the field. Walking today’s spaces with narration and reenactments allows participants to share these histories. The tours aim to inform, ground, and inspire new activism, in the tradition of movement historians like Howard Zinn and Ronald Takaki.

Process Talk: Cynthia Leitich Smith on Harvest House

Cynthia Leitich Smith (see my post on Sisters of the Neversea) returns to the loving embrace of family and community with her YA novel, Harvest House. I was delighted to see Hughie of Hearts Unbroken take center stage here. I asked Cyn if she’d talk to me about the community these books collectively build and how the writing of Harvest House played out for her.

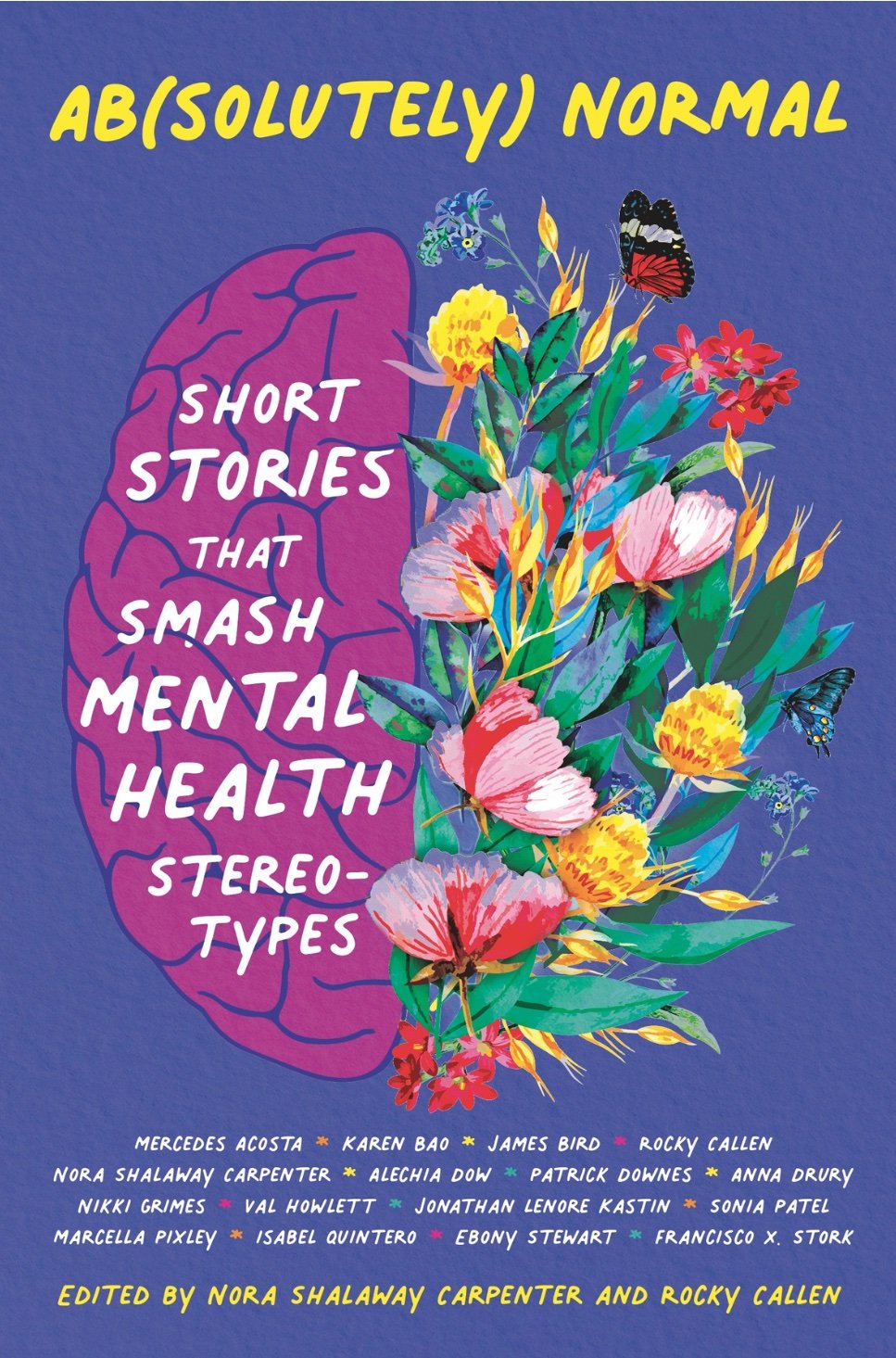

Process Talk: Nora Shalaway Carpenter & Rocky Callen on Ab(solutely) Normal

Revealing and hiding the self, finding who you are. accepting that self and all that comes along with it. Accepting others. Refusing to be denied. These are all human ways of being and yet for some of us life itself comes along with labels. Sometimes these can limit and wound; at other times, defining a problem can set a person free. Many ways, many voices, burst out of the stories in Ab(solutely) Normal: Short Stories That Smash Mental Health Stereotypes.

Looking the Tiger in the Eye

The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable was Amitav Ghosh’s first book of nonfiction after his marvellous travel memoir and quest to unpack history, In an Antique Land (1992).

The opening chapter contains this passage on the Sundarbans, that mangrove forest region where three rivers run into the Bay of Bengal:

The Sundarbans are nothing like the forests that usually figure in literature. The greenery is dense, tangled, and low; canopy is not above but around you, constantly clawing at your skin and your clothes. No breeze can enter the thickets of this forest; when the air stirs at all it is because of the buzzing of flies and other insects. Underfoot, instead of a carpet of softly decaying foliage, there is a bank of slippery, knee-deep mud, perforated by the sharp points that protrude from mangroves roots. Nor do any vistas present themselves except when you are on one of the hundreds of creeks and channels that wind through the landscape—and even then it is the water alone that opens itself; the forest withdraws behind its muddy ramparts, disclosing nothing.

That description transports me there, forces me to care when it would be so much easier to back away from the book’s big questions.