What Makes Us Who We Are? The Ugly Little Boy by Isaac Asimov

Isaac Asimov’s short story, “The Ugly Little Boy,” was one of his own favorites, a tale of a nurse and the little Neanderthal child she’s been hired to care for. In Asimov’s words:

…I have received letters from people who say that they cried when they read the last part of the story, and I always answer and say well I'm glad they did because I cried when I wrote it and in fact I cried when I just read it, so I guess it means something to me.

I read “The Ugly Little Boy” not in its first appearance in Galaxy magazine under the title “Lastborn” but in the Nine Tomorrows collection. The Neanderthal child has been brought via time travel to a specially constructed lab to be studied.

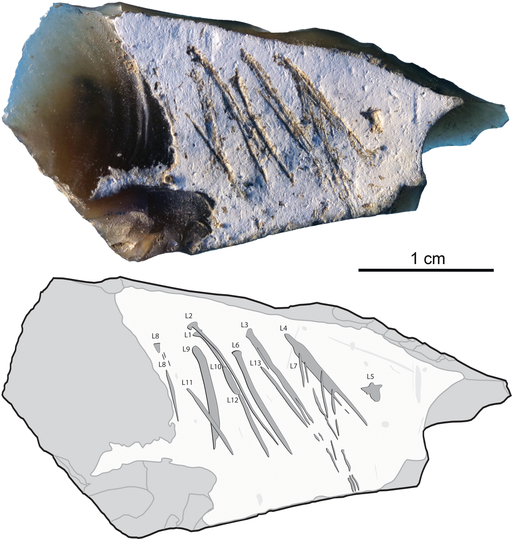

Engraved flint from a Neanderthal child's grave at Kiik-Koba, Crimea, Ukraine. Ana Majkić , Francesco d’Errico, Vadim Stepanchuk, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In its own words, the story explores the “invisible dividing line between the ‘is’ and the ‘is not.’” The Neanderthal child is an experimental subject, but we experience him through the eyes of the woman who rapidly begins to love him. As Miss Fellowes feels her heart lurch, so do we begin to care for this small child ripped from his reality and brought to another world to satisfy nothing more than someone else's curiosity. The parallels in human history are unmistakable.

I was reminded of this story by an article in The Conversation, prompted by the 8-billion mark recently hit by world human population.

Excerpt:

The reasons for our dramatic population growth may lie in the early days of Homo sapiens more than 100,000 years ago. Genetic and anatomical differences between us and extinct species such as Neanderthals made us more similar to domesticated animal species. Large herds of cows, for example, can better tolerate the stress of living in a small space together than their wild ancestors who lived in small groups, spaced apart. These genetic differences changed our attitudes to people outside our own group. We became more tolerant.

Maybe we survived, the article suggests, because we’re more adaptable and because we depend on social networks in times of crisis. Neanderthals would likely not have grown in such numbers, nor would they have driven megafauna to extinction. As for spreading all over the planet…technology… agriculture…extraction of fossil fuels…have we just been too clever for our own good?

In the short story, Asimov depicts the little boy with great care and sensitivity. Empathy keeps us caring for Miss Fellowes and for her little Neanderthal protege. Inevitably, her feelings for the child bring her into conflict with her employer.

Miss Fellowes, it must be said, is a woman of her author’s time, and her passing flirtatious imaginings about Dr. Hoskins read a bit oddly today. I don’t remember noticing that when I first read the story in the 1990s, which raises another whole set of questions about the changing of minds over time and what makes us who we are.

All Miss Fellowes can be, given her circumstances, is sullenly compliant. But the more she finds out about the Stasis project, the more fiercely she is able to declare to Dr. Hoskins that Timmie is human. “Stupid man!” she says to herself, but she goes on caring for Timmie, through the experiments. We get glimpses of needles and tests and food used as a reward, akin to the experiments to which humans have subjected others in our very own, very real past. When Dr. Hoskins develops the ability to reach into near time his new project brings a medieval peasant into the modern world. Only then is Miss Fellowes able to take a stand. When the loudspeaker calls her name, she summons the nerve for her final surprising action—the one that makes readers cry.