Writing With a Broken Tusk

Writing With a Broken Tusk began in 2006 as a blog about overlapping geographies, personal and real-world, and writing books for children. The blog name refers to the mythical pact made between the poet Vyaasa and the Hindu elephant headed god Ganesha who was his scribe during the composition of the Mahabharata. It also refers to my second published book, edited by the generous and brilliant Diantha Thorpe of Linnet Books/The Shoe String Press, published in 1996, acquired and republished by August House and still miraculously in print.

Since March, writer and former student Jen Breach has helped me manage guest posts and Process Talk pieces on this blog. They have lined up and conducted author/illustrator interviews and invited and coordinated guest posts. That support has helped me get through weeks when I’ve been in edit-copyedit-proofing mode, and it’s also introduced me to writers and books I might not have found otherwise. Our overlapping interests have led to posts for which I might not have had the time or attention-span. It’s the beauty of shared circles.

Looking the Tiger in the Eye

The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable was Amitav Ghosh’s first book of nonfiction after his marvellous travel memoir and quest to unpack history, In an Antique Land (1992).

The opening chapter contains this passage on the Sundarbans, that mangrove forest region where three rivers run into the Bay of Bengal:

The Sundarbans are nothing like the forests that usually figure in literature. The greenery is dense, tangled, and low; canopy is not above but around you, constantly clawing at your skin and your clothes. No breeze can enter the thickets of this forest; when the air stirs at all it is because of the buzzing of flies and other insects. Underfoot, instead of a carpet of softly decaying foliage, there is a bank of slippery, knee-deep mud, perforated by the sharp points that protrude from mangroves roots. Nor do any vistas present themselves except when you are on one of the hundreds of creeks and channels that wind through the landscape—and even then it is the water alone that opens itself; the forest withdraws behind its muddy ramparts, disclosing nothing.

That description transports me there, forces me to care when it would be so much easier to back away from the book’s big questions.

Growing into a Name

In The Boy Who Tried to Shrink His Name, Malayali-Australian writer Sandhya Parappukkaran endows her protagonist with the long, long name promised by the title. The name is “long like shoelaces that always come undone,” says the boy. “It trips me up every morning.”

In Search of Structure

For John McPhee, it started with a picnic table.

Me, I’ve been staring at a 2 ft. x 3 ft. piece of cardboard, hoping to find a way to pin down the structure of the nonfiction book I'm working on. I have a thesis that emerged from my proposal for the book and was more or less confirmed by the draft. I have a synopsis I put together when I was halfway through, revising it along way. Those will go onto that cardboard. They'll help me stay on track so the draft manuscript deliver in a few months won't be a red hot mess.

“Words are the Only Victors”

“Words are the only victors,” writes Pampa Kampana, at the end of Salman Rushdie’s new novel, Victory City. It’s his twenty-first book and it is, among many other things, a celebration of words.

Remembering Father Brown

In the 1960s, when I used to go visit my grandparents, first in Bombay, then briefly in Madras, and finally, before my grandfather died, in Bangalore, I’d look forward to long, uninterrupted hours of reading. My Thatha had collections of P. G. Wodehouse (first editions they were, some of them—I could kick myself for not being bold enough to ask for a few when I had the chance. I’m sure he would have given them to me and I have no idea what happened to them. He had endless volumes of Agatha Christie and the entire Sherlock Holmes Long and Short Stories by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

He had another set of books by G. K. Chesterton, with a “dull” and “very short” Catholic priest from Essex as the unlikely PI character in a series of mysteries no one else could crack.

Prose and Possibility in The Last White Man by Mohsin Hamid

In the manner of Gregor Samsa in Kafka’s Metamorphosis, Anders, the protagonist of Mohsin Hamid’s novella, The Last White Man, wakes up to find himself transformed. He’s not a bug, however. As you might expect from the title, Anders has turned brown. We’re never quite sure why—there is some speculation that there was something in the water—but brown he is, “a deep and undeniable brown.” Soon others begin turning brown as well.

Rereading Earthseed in a Time of Planetary Change

Whatever I happen to be working on, I usually find myself needing an antidote in my reading, something that works against the grain of the writing.

Being in the depths of nonfiction at the moment, I needed to read fiction. But I wanted to read fiction that was capable of speaking to reality in the way that Richard Power’s Overstory did for me.

That is why I find myself rereading Octavia Butler’s iconic Earthseed novels, Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents.

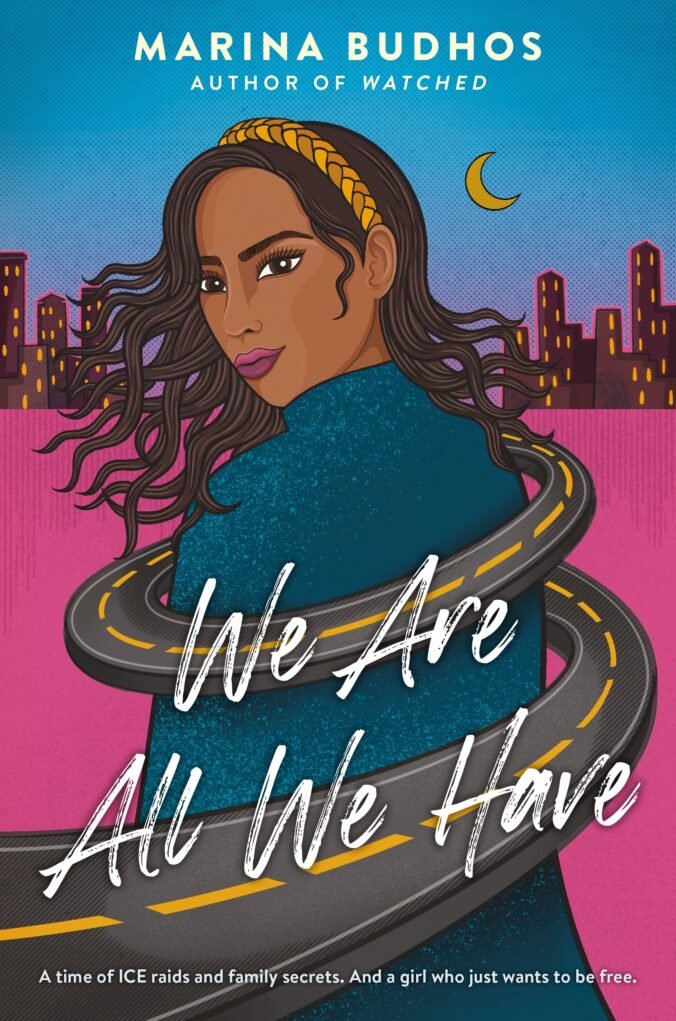

How Else Can We Think About Migration?

In her book, Resident Foreigners: A Philosophy of Migration, Italian professor Donatella Di Cesare questions the idea of the exclusionary state. She asks, is migration not a fundamental human right? Are we not all temporary guests—tenants, in fact—on this only earth of ours? What purpose, then—whose purpose—do borders serve?

The Death of Volodymyr Vakulenko Should Hit Very Close to Home

Volodymyr Vakulenko was one of us. He was a children’s writer. He posted to Wikipedia. He kept a journal during the Russian occupation of Kharkiv. He buried it under a cherry tree when it seemed as if they were coming for him.

Who Will Speak for Trees? The Overstory by Richard Powers

Why begin a new year with thoughts of the end of the world as we know it? Because human voices have spoken enough untruths, it seems right to hand at least some of our narrative over to those we have always assumed to be silent.

Trees speak in this novel, which seems fitting, since in the real world we refuse to give them voices.

Waiting 187 Years for Representation

Over the years, I’ve come across these children’s books by writers from the Cherokee Nation:

Mary and the Trail of Tears: A Cherokee Removal Story by Andrea L. Rogers

The Reluctant Storyteller by Art Coulson with Traci Sorell

And of course Traci Sorell’s many lovely books.

I thought of these writers and their books and of stories yet to be written when I spotted this article from National Geographic, a publication that now seems committed at last to making up for its own many past wrongs.

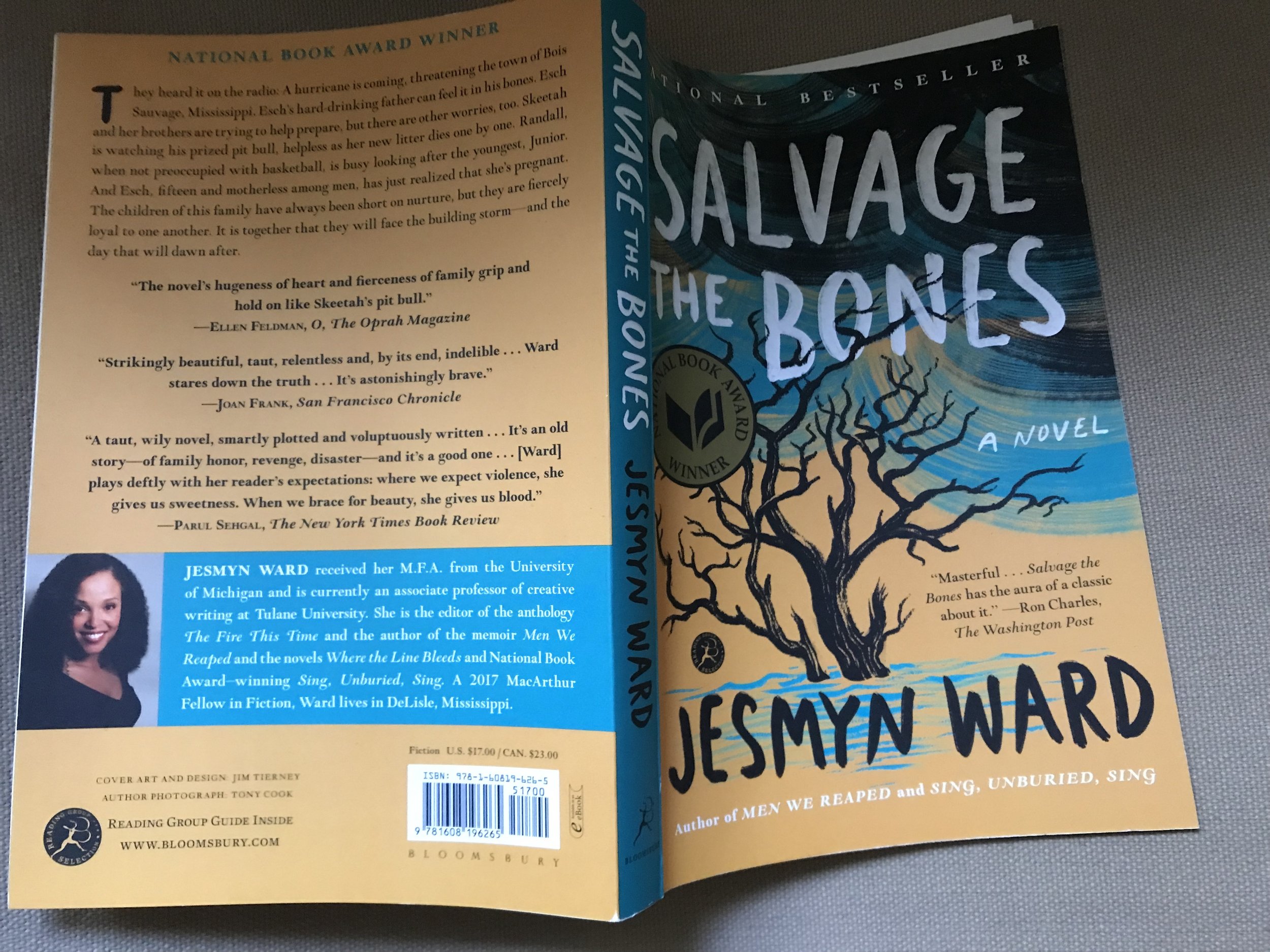

Reading Salvage the Bones as a Climate Novel

Jesmyn Ward’s Salvage the Bones, 2011 National Book Award fiction winner, is among the tidal wave of titles hit by book bans in the Disunited States. It happens that this is also a climate change novel—not that the book banners raised that particular point.

Consider the storm…

Reunion by Fred Uhlman: the Brilliance of Narrative Economy

“He came into my life in February 1932 and never left it again.” A friend in England recommended Reunion by Fred Uhlman and sent the book along for good measure. It is such a slender novella that I started reading it out loud—and found that I could not stop.

How is it that I have never come across this book before?

On US Election Day, Here’s a Sentence to Reflect Upon

A couple of months ago, this item from People magazine showed up in my newsfeed: “First Politician Involved in January 6 Capitol Riots is Removed from Office Following Judge's Ruling.” It was the first time a judge officially labeled the events of January 6 an "insurrection." It was also the first time since 1869 that a U.S. official was disqualified from public office under Section 3 of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution.

I read the item quickly, grateful for justice taking its course and expecting to move on to the next news item and the next, as one does over morning coffee.

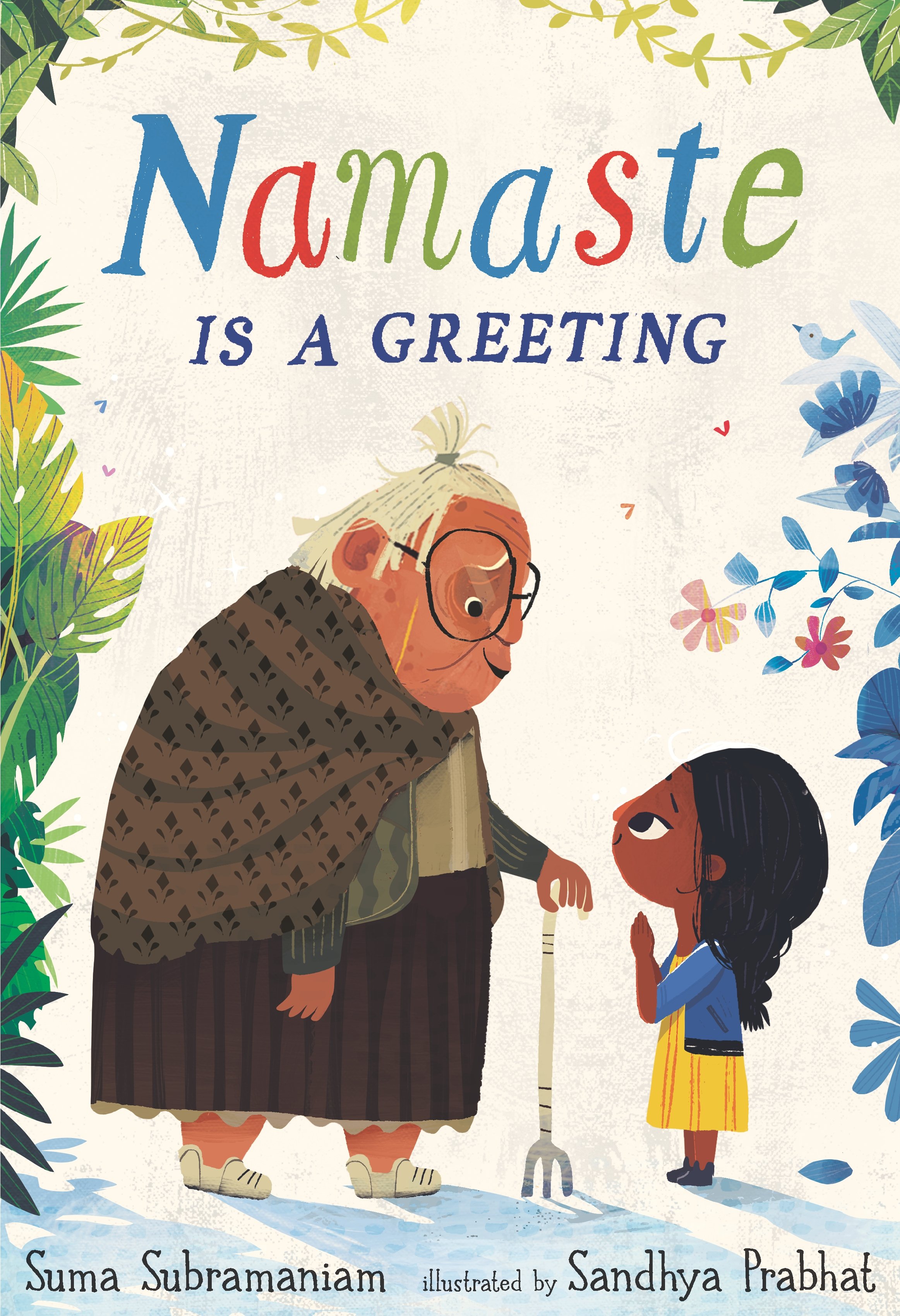

Guest Post: Suma Subramaniam on Namaste is a Greeting

Honoring the Good by Suma Subramaniam

The objective of Namaste is a Greeting is to understand the meaning of the word “Namaste” and the value it can bring when it’s spoken verbally and expressed non-verbally. Namaste in Sanskrit is a combination of two words—namah, meaning “bow,” and te, meaning “to you.” Therefore, namaste is a greeting that means “I bow to you.”

Whimsy and Loss in Bone Dog by Eric Rohmann

Confession. I am not a lover of dogs. I accept that humans have domesticated them for eons, but I’m not a fan of slobber and the wagging tail holds few charms for me.

Even so, here’s one dog picture book that I found purely enchanting.