Process Talk: Kao Kalia Yang on Generous Memoir and the Dance of Picture Books

For me, the art of making the picture books is much like a dance, an orchestration of my words with someone else's images. I lead. I follow. We move together across the page. Kao Kalia Yang

Kao Kalia Yang is a poet, teacher, speaker and the author of three picture books written from the depths of her own experience as a Hmong American woman. Her debut children’s book, A Map Into the World is an American Library Association Notable Book, a Charlotte Zolotow Honor Book, winner of the Northstar Best Illustrator Award, and winner of the 2020 Minnesota Book Award in Children’s Literature.

I encountered Kalia's work when I had the honor of judging the McKnight Artist Fellowship in Children's Literature earlier this year.

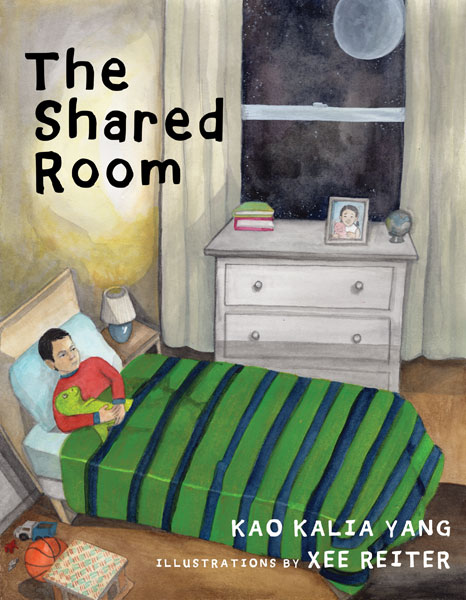

I asked Kalia to talk to me about her picture books, including her new one, with this jewel of a jacket image:

[Uma] Kalia, what's the relationship between poetry and picture books for you?

Photo courtesy of Kao Kalia Yang

[Kalia] I come from a strong oral tradition. From a young age, I was taught that words must be able to write on memory. As well, the Hmong language is a tonal language; every breath I breathe into the world carries meaning. In this way, my use of language tends to live on the poetic possibilities--the way words look and the way they sound matter. For me, the art of making the picture books is much like a dance, an orchestration of my words with someone else's images. I lead. I follow. We move together across the page. It is the flow and it is energy we create together that constitutes the final thing; it is not until the music ends, when we are breathless and free from the movement that the work is done. The very best picture books have always been like poetry to me. They make use of the air in my lungs and take me into a seamless performance between words and images.

[Uma] The structure of your stories is fascinating to me. They turn unexpectedly, and the patterns they create recur in interesting and surprising ways. Can you talk about using the story cloth image in A Map into the World, say, or the beautiful connection of the child’s hands on the grandmother’s feet in The Most Beautiful Thing? How did these images fall into place for you and how did they become so integral to the story’s structure?

[Kalia] In A Map into the World, it was very important to me that I write a story about a Hmong girl and her life in America--not the story so much of how she got here. I love the story cloth because it is such an integral part of the Hmong culture as a way of documenting the past and dreaming into the future--so I knew I wanted to name my protagonist Paj Ntaub. The story cloth, in my conversations with my own children, emerge as a kind of map for being--not just where to go but how to go. These aspects were important to me and I wanted to preserve them in the book because they are true to our lives but also represent so beautifully the experiences of first and second generation immigrants and refugee children. The things our parents carried are the things we used to become, make sense of, and build with in the new places we call home. My hands as a child held and hugged my grandmother's feet. The way her skin felt and the way my skin felt were the early contrasts in our relationship. I wanted to honor these facts and also enter into them fully for The Most Beautiful Thing. Much of my relationship to structure is built on my relationships to the people whose very lives have inspired and compelled me to tell their stories. My hands knew the feel of her feet more than my words, thus I needed the image to fulfill those long ago but persistent memories.

[Uma] “A melt in the freeze of their hearts.” What a beautiful line that is, and how it makes that family a single collective voice in The Shared Room. The conventions of western children’s books push us toward seeking a single protagonist. Here, this family, together, are the character. They move us precisely because they hurt and heal together. Your thoughts?

[Kalia] From my very first book, I was interested in pushing the form of the memoir to be a more generous thing than it has traditionally been in American and western literature. Traditionally, the memoir is a form that belongs to the rich and famous, the illustrious individuals whose lives were of supposed interest. For me, that could never be what memoir was. So, in my very first book, I wrote The Latehomecomer and called it a family memoir. In this way, The Shared Room, continues the work that I started way back when I was still quite young, 22 years old. In a more particular war, the book is a story of grief. Grief is a shared experience in a family. To be true to that reality, I had to call on the single collective voice of the family.

[Uma] Every book teaches the writer something. What did you learn from writing each of these books?

[Kalia] A Map Into the World taught me how to stretch the seasons and make them longer, make them last on the page even as I and my characters acknowledge and grow with their passing. The Shared Room taught me how to carry grief as a member of a community without caving in, how to weep in the world of the picture book with my characters and my readers. The Most Beautiful Thing teaches me that every elder is a treasure trove of stories and to untangle the threads of one leads necessarily to the other. Grandma's stories are not done. There are no happy endings in a story where a child dies, but there are many reasons to nurture the fire she'd lit with her life. All the things we love and have stored in our hearts will be for others, in their moments of need, maps and story cloths for the life that is still here. The books have taught me in process, they teach me still now that they are in the world and in the hands of readers.

[Uma] What sustains you in this work?

[Kalia] It is a great joy to write for children. It is fun to travel through the layers of experience and the debris of the years to unravel for myself the magic of my own childhood, to open myself to the experiences of my own children and the world they are now living and growing in. To write for children is to offer up my imagination and my heart to the little stories that form the bigness of the world. It is a gift I cherish.

Thank you, Kalia, for sharing your unique and stirring perspective.