Process Talk with Jen: Uma Krishnaswami on Look! Look!

[Posted by Jen Breach for Writing With a Broken Tusk]

In Uma Krishnaswami’s own words on her book Out of the Way! Out of the Way! (Groundwood, 2010), after many drafts based on editorial feedback were tossed aside that had insisted the story be more plot-based, more in line with mainstream US children’s publishing: “I told the story the way it showed up in my mind, with a long timeline, a single action taken by one young boy, and the place itself as the center of the tale. It became a story about a child in a community, about the power of a single action unleashing a long spiral of consequences. It relies on repetition, on rhythm, on auditory effect, as much as it does on the beautiful illustrations of my almost-namesake, artist Uma Krishnaswamy from Chennai.”

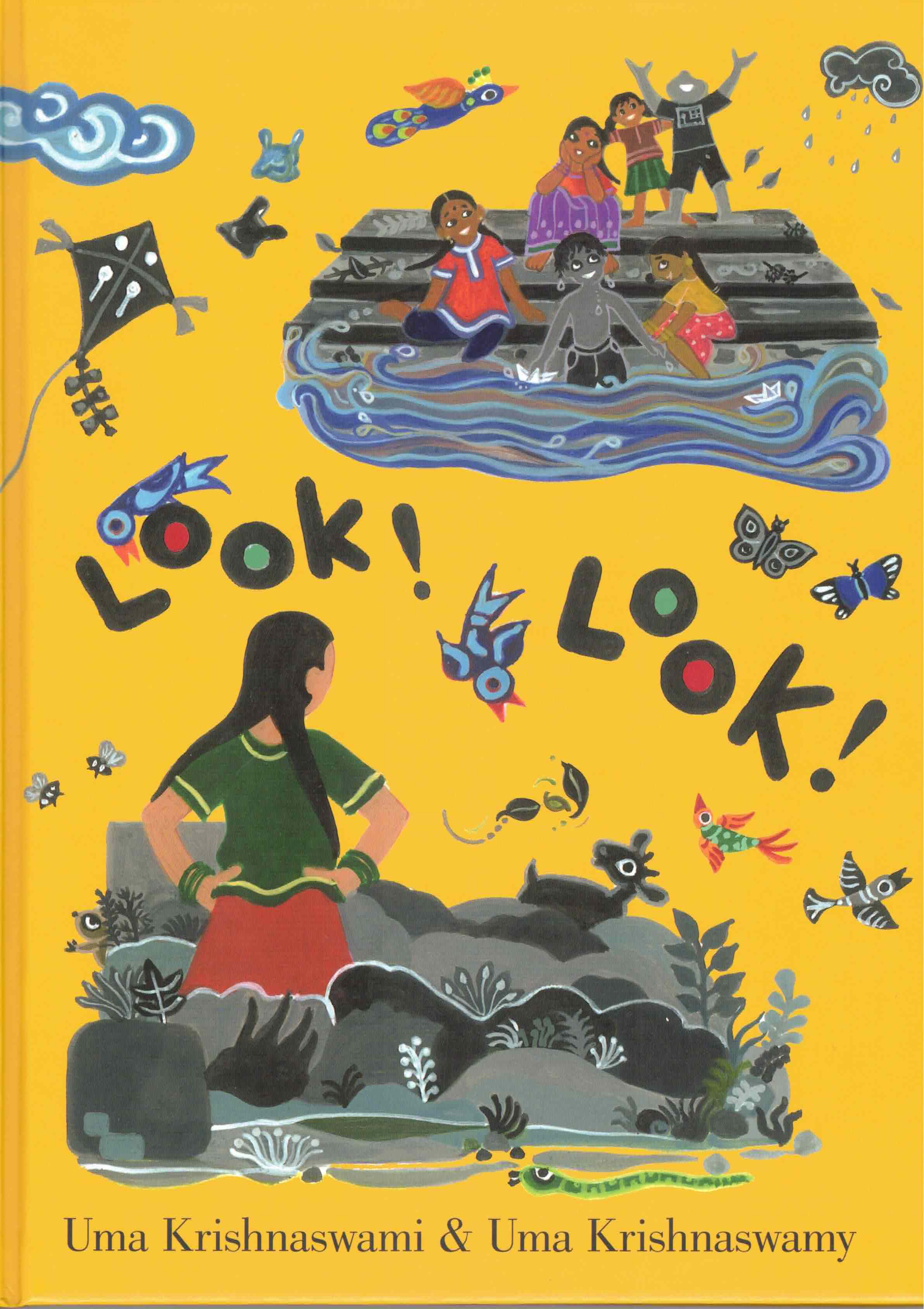

Now, Uma, Uma, and Groundwood return with the companion title Look! Look! and we toss up streamers and snap on party hats to celebrate its release.

[Jen] Out of the Way! Out of the Way! ends with the idea of remembering stories from our community elders through the lens of a tree, and Look! Look! begins with finding one such forgotten story about water. How do natural elements–trees, water, earth as both tree-nurturing and weed-sprouting–link to story in your writer’s mind? And how do they link to the passage of time?

[Uma] I have always found something both magical and humbling in the way that natural elements struggle to cope and endure in the environments that we humans alter. We keep stamping them out carelessly—we cut down trees, dam rivers, dredge wetlands. And still, when we pull back on our bad habits, when we give them a hand, they are capable of returning. That’s a huge understanding. It’s what drives today’s efforts to rebuild coral reefs, regrow mangrove trees, build rain gardens in cities. We’ve spent centuries pitting human ingenuity against natural processes as if the earth itself were an enemy to be subjugated. And yet, we know, don’t we? Put a few rocks around a sapling and it might grow into a tree. Dig up an old well and you might discover what it once did and perhaps could again.

But these are not quick fixes. They need time and their effects won’t be known without waiting and paying attention. That’s why I needed to understand the role of time in these stories. I should tell you that time and I have a rather fraught relationship. I have terrible trouble with timelines and sequencing in my longer fiction and copy editors always have to come in and troubleshoot. What, three mornings in a row (or two Tuesdays)? How long does all this take anyway? But seeing the role of time in Out of the Way! Out of the Way! made the story fall into place for me. So of course it felt like a natural element of Look! Look! as well.

[Jen] Out of the Way! Out of the Way! is about a boy whose act of quiet defiance ultimately benefits his community. Look! Look! is about a girl who directly invites her community to participate in a beneficial action. Can you speak about the difference you see, if any, between a child’s agency in 2010 and now?

[Uma] What a wonderful question! The 2010s became the birth decade for youth activism, so I’d say there’s a big difference between then and now. What’s even more interesting to me is this: I never realized the difference that you point out between the two books. You’re absolutely right, it is the difference between quiet defiance and being unafraid to use your voice. The girl in Look! Look! takes for granted that the community will listen to her and support her. That’s not to say that children in the real world always get listened to—far from it. Children still remain among the most vulnerable people in the world. But it is certainly a shift in my own thinking, and one that I wasn’t even aware of, so thank you, Jen.

[Jen] It feels like a natural companion approach–two ways to make a difference.

Your author’s note for Look! Look! explicitly refers to climate change. Rather than beating one over the head with a capital-m Message about the climate crisis, you have created an invitation to pay attention. Not an easy thing to do! Can you speak about how you honed (or are in the processing of honing) that craft skill?

[Uma] Oh, how I absolutely want to beat people over the head about climate change! That’s when I’m not weeping about it. But I have to keep in mind that I am speaking to children in my books. Our young readers had nothing to do with the creation of this crisis. That opprobrium belongs to the fossil fuel industries and the governments that supported and indulged them, thus creating economies from which we now seem unable to extricate ourselves. But unfortunately, those same young readers are going to inherit this mess. The least I can do is present my stories as invitations to community. I find myself doing that at some level in all of my fiction—I guess I do believe that the only way we’re going to make it into the future is if we work together. Maybe that’s why I’ve always resisted the storyline of the singular hero winning the big prize as a template for fiction. It’s always felt like a very selfish storyline, whereas I’ve been more drawn to resolutions that involve collaboration and community.

[Jen] So well said, Uma.

You have also written eloquently about how special it is when a writer can invite you to a geographical location you’ve never been to and make it fully realized. I feel the same way about the Indian village life you describe in these books and elsewhere. What is important to you that we US and Canadian readers understand about India through the text?

[Uma] That it’s always changing. There’s a tendency to see faraway places in static frames. Even in the 21st century, India is often symbolized in the West by spices, maharajahs, oppressed peasants, tigers slinking through undergrowth, sunset shots framing exotic ruins, flooded coastlines—can you feel the shorthand at work in those images? But in reality it’s a bustling, colorful, vibrant, incredibly diverse country, full of very opinionated people, full of families, full of children with beautiful, ringing voices. I want my words to touch readers with that shifting, changing energy of a place that’s struggling and surging, always in tension with its past and present, perpetually transforming itself. And the children, the children! I want to keep them in the foreground, always.

[Jen] You have certainly achieved that foregrounding in these marvelous books. Thank you and congratulations!

[Uma] Thank you, Jen. 🙏🏽