Process Talk: Heather Camlot on The Prisoner and the Writer

I don’t remember where or when I first heard of The Dreyfus Affair—the wrongful conviction and imprisonment of Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer attached to the French General Staff, on charges of military espionage and selling secrets to the Germans. It might have been included in one of those Reader’s Digest Condensed Books that I devoured, reading scaled-down versions of dozens of titles that I’d never have found otherwise in my childhood years in India.

I can’t remember, but at any rate, here’s the quick version: Dreyfus was found guilty of treason and sentenced to life imprisonment on Devil's Island, a notorious colonial French prison off the coast of French Guiana. For more than a decade, a small group of human rights activists worked to clear his name, among them author Emile Zola. The real culprit was identified and Dreyfus was eventually pardoned.

Image courtesy of the author

Decades after I first heard that story, I’m delighted to be talking to Heather Camlot, author of The Prisoner and the Writer, a beautiful middle grade book in verse about the exchanges between Zola and Captain Dreyfus, which led to Dreyfus’s eventual release.

[Uma] With so much documentation and historical information, how did you decide where to begin the story?

[Heather] The heart of this story, for me, is antisemitism, social justice, and advocacy – all of which I tend to write a lot about. So it made sense to start in 1895 with the problem, with French Captain Alfred Dreyfus banished to Devil’s Island for a crime he didn’t commit but made the scapegoat simply because he was Jewish. Emile Zola hadn’t much heard about the Dreyfus Affair because he had been doing research for his next novel. Rather than detail the next two years, I jumped to 1897, to Emile Zola’s entrance into the Dreyfus Affair and the fight he was about to undertake.

[Uma] Tell me about other choices you made in writing this book and what determined these choices.

[Heather] The book juxtaposes what was happening with the two men as Zola fought for Dreyfus. This idea came from Groundwood publisher Karen Li. She saw some parallels between the men in my original draft and we then worked out whether I could alternate spreads about them. It was amazing how many similarities there were, how many connections they had even though they didn’t know each other; both of them going to court because of the Affair, both of them being called horrible names by their fellow countrymen, both of them leaving France for a time, and more.

Antisemitism, social justice and advocacy were my main drivers, so my choices centered on those themes. Zola clearly saw through the biased, fake news of the day, clearly saw the ugly power of antisemitism and military might. The Prisoner and the Writer is a story about standing up and speaking out against injustice, and how Dreyfus, Zola and their supporters never gave up when there were so many moments that they could have just said ‘I can’t do this anymore.’ The book ends on a positive note, but there is so much more to the story. Isn’t there always? That’s why readers will find an author’s note, which explains how the Dreyfus Affair remains current, and short essay about the power of the press (a lesson in media literacy) at the end of the book.

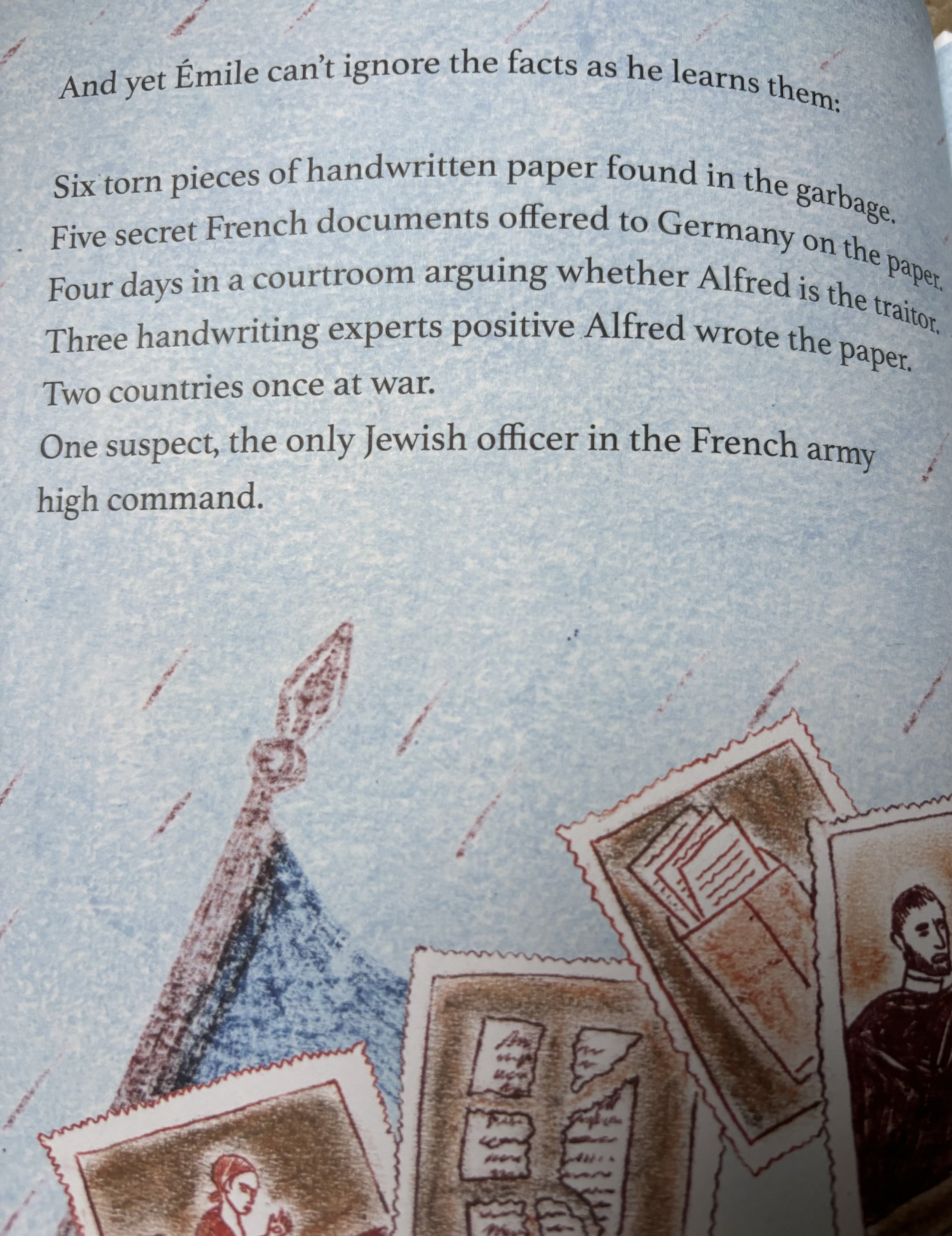

[Uma] I love the page with the descending numbers—it rattles us through the facts of the case in such a compact, dramatic way. You often use poetic conventions (that’s a list poem right there) to tell a very complex historical tale. Talk about your use of poetry as the vehicle for telling this story.

[Heather] Thank you! I’m very happy with that spread as well. It wasn’t in the original draft, but as I did more research, I noticed the number pattern and thought it would be a clear and concise way to convey the basic information of Captain Alfred Dreyfus’s court martial.

I had never used poetry or verse to write a book before. It was new to me and to be honest, I didn’t really know that’s what I was doing when I started. I wanted to make the complex story as easy to digest as possible without compromising the seriousness of what was at play, at what was at stake. Depicting what was possible and not possible through the use of the words “can” and “can’t” allowed me to get to the core of the story. The white space of poetry and verse gives readers the room to breathe, to take a minute to reflect.

Heather Camlot and Sophie Casson at Groundwood’s bookstore. Photo used by permission of author and illustrator

[Uma] The books sits wonderfully in the hand, with the size and feel of a journal. The art lends expressiveness and movement to the text. Can you tell me your thoughts on how Sophie Casson’s prints and pastels and the book design all add to your text?

[Heather] Because The Prisoner and the Writer is for readers age 8+, Karen Li (publisher at Groundwood Books) explained that it would be better to depart from a picture book look and feel. That differentiation started with the size of the book. It does feel like a journal as you note, or a graphic novel. I think the size brings the story closer to the reader, both physically and mentally. It’s literally in your hands – just like standing up and speaking out. Sophie Casson’s gorgeous art also reflects an older look and feel. She did a lot of research to capture the mood of the Dreyfus Affair and the great many details of the late 1800s. Her palette is dark to mimic the goings-on, but she also bathes certain scenes in yellow light to let readers know that hope is alive and well. The illustrations are monotypes with oil pastels. It’s quite amazing work as you can only use a monotype once. I had the opportunity to visit Sophie at her studio in Montreal, where she showed me the process as well as the originals. I am very lucky to have had this opportunity to work with Sophie, Karen and the Groundwood Books team. Everyone involved did an incredible job in bringing the more than 125-year-old story of Alfred Dreyfus and Emile Zola to life for a new generation.

[Uma] I’ll end with this quote from the book. This is the moment when Zola realizes what he must do: “…he can’t engage/ From the sidelines any longer./ Not when he has a voice to speak./A hand to write./ The courage to act./The power to persuade.”

Words to live by. Thank you, Heather Camlot.