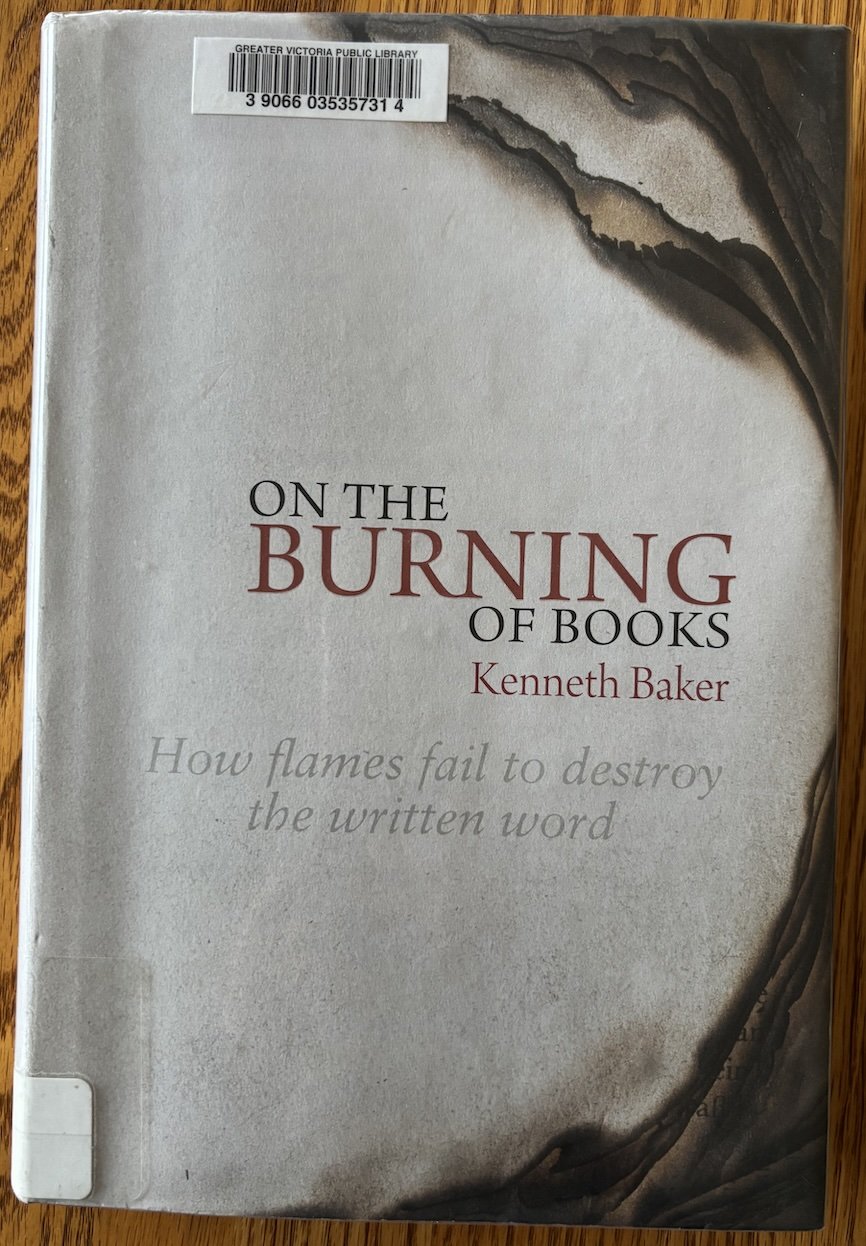

On the Burning of Books: Kenneth Baker’s Illustrated History of Book Burning

The subtitle of Kenneth Baker’s gorgeously illustrated history of book burning, mostly focusing on Europe and North America but with a few nods to events elsewhere, carries a lyrical note of hope:

How flames fail to destroy the written word.

Breathe that in. I hope the premise holds.

In our age of division and conflict, in a time when so many people around the world are retreating into their own little corners of religion and ethnicity and ideology, I read this book looking for the long view.

The book itself is a celebration of its medium. It’s heavy, for one thing. You can’t easily hold it up, say, for a bedtime read. I found it best to read it in daylight, when the beauty of its glossy pages dazzled me, inviting me to linger a while before delving into the events chronicled in the book. From Savonarola’s execution in 1498 to Italian Fascist and Nazi destruction of books on an industrial scale, to the British formation of teams “of European descent” to burn any documents that might embarrass the government and offer evidence of the brutal suppression of rebellions from Kenya to Malaya—all that and more is in a section titled “Political Burning.”

“Religious Burning” offers a similarly wide-ranging array, making it clear that believers of all stripes are capable of hating those whose expressions of life and mind and eternity (or lack thereof) may vary from their own. Thus a spread where Dubliners by Jame Joyce and The Country Girls by Edna O’Brien face Salman Rushdie’s famously banned/burned/condemned novel, The Satanic Verses.

“War Burning” includes multiple assaults on the Library of Alexandria, where rolls of papyri were used to fuel the public baths for months, the Sack of Constantinople in the 13th century, the 1814 burning of the Capitol in Washington, and more. That books were an inevitable target of the violence of war is a type of collateral damage that Baker documents with clear regret. The shelling of the library in Sarajevo traces the spiralling of what was once a multicultural state into a place where “fanatical and in this case ethnic bigotry attempted to distort history.”

“Personal burning” lists memorable anecdotes like the burning of Sir Richard Francis Burton’s most explicit writings by his deeply religious widow, Thomas Hardy’s destruction of his own early drafts and T.S. Eliot’s determination to destroy personal letters so as to leave behind as little biographical material as possible.

“Accidental Burning” holds surprises—a maid burned the manuscript of Thomas Carlyle’s The Bastille, thinking it to be trash. I found the most compelling account in “Royal Burning” to be the tragic destruction of Queen Victoria’s letters to Abdul Karim, the “Munshi” we know from the movie Victoria and Abdul, the burning spurred by the royal family’s racist, snobbish hostility toward him.

The book wraps up with “Lucky Escapes,” from Dylan Thomas’s lost manuscripts of Under Milk Wood to the volumes that managed to survive Gerard Manley Hopkins’s renunciation of poetry for Lent. Here are those as well who ignored the wishes of dying writers to destroy their remaining work (Augustus countermanding Virgil’s desire to destroy the Aenid; Kafka’s friend, Max Brod; Katherine Mansfield’s husband, John Middleton Murry).

A lovely find for bibliophiles.