Histories No One Taught Me: the Story of Yasuke, African Samurai

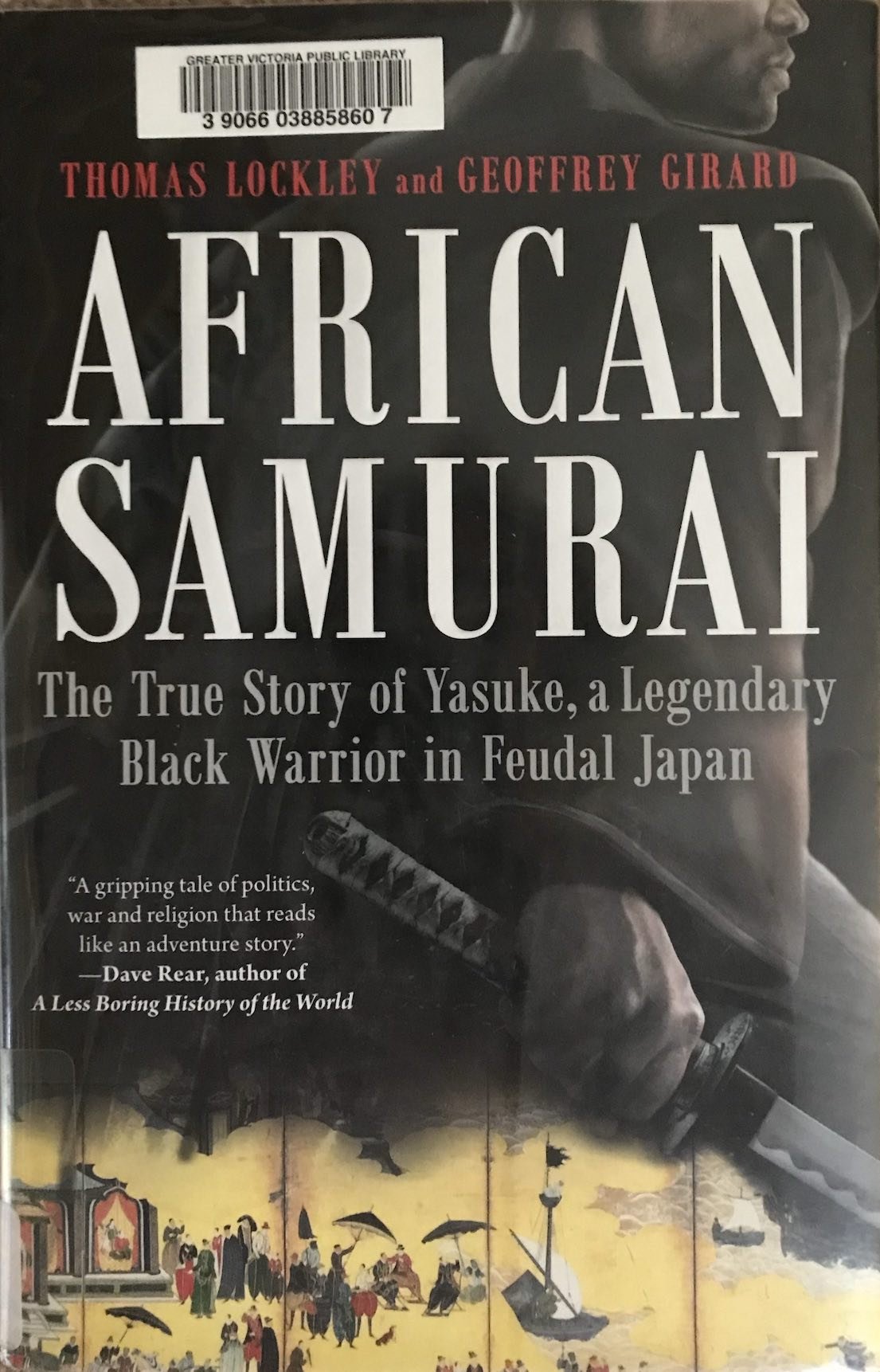

African Samurai: The True Story of Yasuke, a Legendary Black Warrior in Feudal Japan by Thomas Lockley and Geoffrey Girard is a deep dive into the story of a little-known historical figure: an enslaved man from East Africa transported by the Portuguese to Japan, left behind there with a Jesuit mission. He came to be known as Yasuke, and fought alongside feudal lord Odo Nobunaga to become Japan’s first foreign-born samurai.

I don’t remember where I first heard about this book. Possibly, it was on one of the many little off-ramps from the main stories in that wonderful podcast, Empire, hosted by Anita Anand and William Dalrymple. A nod to the Portuguese, perhaps, or a geographical sidestep from the Russian Empire? Anyway, the story intrigued me enough that I looked for the book and am just emerging from its extraordinary pages.

Yasuke was kidnapped as a child, and ended up as servant and bodyguard to Alessandro Valignano, head of the Jesuits in Japan. The book is full of meaningful stuff like this:

While Alessandro Valignano’s name means almost nothing today, in the late 1500s, it moved armies, assembled fleets, and raised cities. He’d been given the official position “Visitor to the Indies” by Pope Gregory XIII and was then dispatched to inspect and develop the flourishing Catholic footholds in India, China and, finally, to the easternmost of the missions, Japan. An enigmatic place the Chinese referred to as the Land of the Rising Sun but largely ignored and avoided, a land of pirates and disorder. Valignano’s first stop there was to be Nagasaki, a deep anchorage in a Jesuit-friendly province. From there, he and Rome hoped the rest of Japan awaited.

Meticulous attention to detail renders the battle scenes nothing short of terrifying. It also centers Yasuke’s presence and manages to maintain it within the larger scope of the history. And the ending, even when it’s clear that historical sources have faded away, is a study in voice and veracity in nonfiction writing, laying out the narrative options while remaining transparent about the lack of finality.

I had no idea about the extent of the proselytizing, arms-dealing (yes, really) Jesuits’ juggling for power and influence in 16th century Japan. The book offers eye-opening perspectives on how interconnected the world has always been and how the simplifying of history erases important chapters of it. Mind-blowing fact: the Jesuits brought along two cannons as gifts. Locals named the weapons kunizukushi or “nation-destroyer.”

There was no one for a hundred miles who knew more about these weapons [than Yasuke].

Of course, I was especially drawn to the passages on Yasuke’s time in India.

He was now a member of a military caste called Habshi—African warriors, often horsemen, who fought for local rulers or were loaned out by a mercenary band leader to whomever was willing to pay. Some of these bands numbered in the thousands, but most were only a few hundred strong. The Indians called the Africans Habshi – a word derived from Abyssinia, the ancient name for Ethiopia – because the large majority of the Africans destined for India had started their sea journeys there. It is estimated that as many as eleven million Africans were trafficked to India as slaves, primarily to be used as soldiers. During this time, when soldiers were in peak demand, estimates reach into the tens of thousands.

Turns out the descendants of some of these Africans are in India still.

As I close the book, I can’t stop thinking about this boy, taken from his village and family, perhaps ten years old or younger. That scene too is brilliantly imagined in flashback, established with precise detail, its inferences carefully laid out in chapter notes.

A novel based on the life of Yasuke by Craig Shreve, titled The African Samurai, is out in paperback this year. See also the Netflix fantasy retelling.