Guest Post: Srividhya Venkat on Seeker of Truth

Kailash Satyarthi’s campaigns against child labor and advocacy for the universal right to education earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 2014, when he was co-recipient along with Malala Yusufzai.

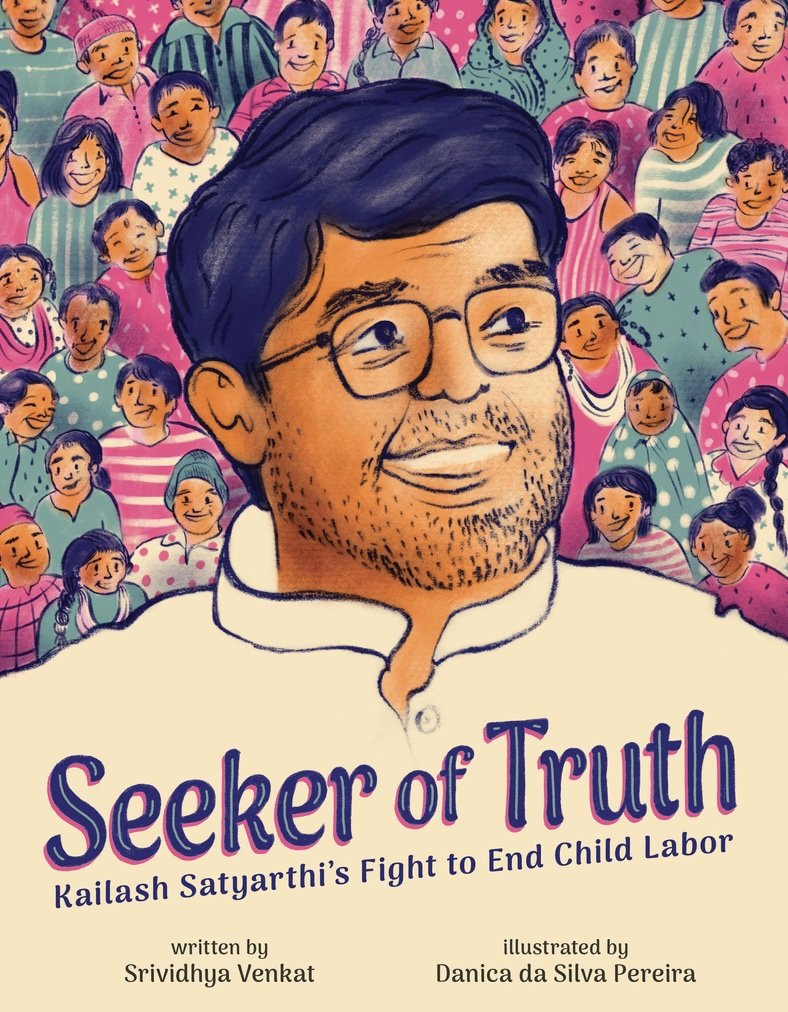

I was delighted to hear of Srividhya Venkat’s picture book biography, Seeker of Truth: Kailash Satyarthi’s Fight to End Child Labor. Her publisher sent me an e-galley of the book, and I ended up writing a jacket blurb—not something I agree to do that often!

Here’s Srividhya on how she overcame her own doubts and questions and decided this was a book she needed to write:

Image courtesy of Srividhya Venkat

I first learned about Kailash Satyarthi four years ago from the back matter of a picture book about Malala Yousafzai, with whom he shared the Nobel Peace Prize in 2014. I was surprised that I had not heard about him earlier, given the magnanimity of his work as a child rights activist and social reformer.

Kailash Satyarthi’s compassion, courage, and selflessness touched my heart. Here was a simple man who had dedicated over 40 years risking his own life to rescue children from child labor and empowering them with education to become future leaders.

Kailash’s story brought back memories of my own childhood in India, where I had seen children working in households and selling chai on railway platforms. But at the time, I did not question why those kids had to work.

Now, eager to learn more about Kailash, I looked for picture books about him, but was disappointed to find none. I couldn’t help but wonder why there were so many books about Malala, and not one about Kailash. Would a children’s picture book about child labor be “inappropriate”? But young readers needed to know the challenges confronting other children. Besides, Kailash’s story was inspiring and empowering. Why hadn’t anybody written about him? And then it struck me. I’m a children’s writer…I will write about him! And that’s how I got started.

As I began a deeper exploration of child labor, I was devastated to find the range of economic and social pressures that lead children to leave their families and go to work in far-off places. Children are often forced to work long hours in dangerous jobs at unsafe places (like mines, quarries, and factories). They endure physical abuse and other traumatic experiences. At one point, I stepped away from my research, feeling emotionally exhausted. My mind brimmed with self-doubt and questions. Did I have the strength to write about such a heartrending issue? Could this even be a children’s book? In my efforts to make it child-friendly, what if I downplayed or disrespected the suffering of enslaved children?

One day, I stumbled upon a book on Kailash self-published by Rosie Katz, 7 years old, who met him when he visited her school. Her art and words revealed how much he had inspired her. I thought, if a little girl had the courage to write about child labor, why was I doubting myself? Kailash’s story had to be told!

In the end, I realized I was writing Seeker of Truth because I wanted young readers to know that all children don’t lead similar lives, and many lack the freedom we enjoy. I want them to know how one man did something about it and helped spark a movement around the world, changing the lives of thousands of those children and giving them the freedom they deserve.

It is my hope that my book will inspire curiosity, empathy, and the courage to speak up against injustices around us.

Here is a man whose childhood sensitivity to injustice led him to work against it all his life, "little by little, drop by drop.” Interior musings of the young and growing Kailash (e.g., “What can I do” “Why aren’t all people given respect?”) offer readers a way to access the strength of the compassion that drives him, and contextualize the enormous social problems he finds ways to take on. Congratulations, Srividhya Venkat, on this lovely picture book biography and thank you for your reflections on writing the book.