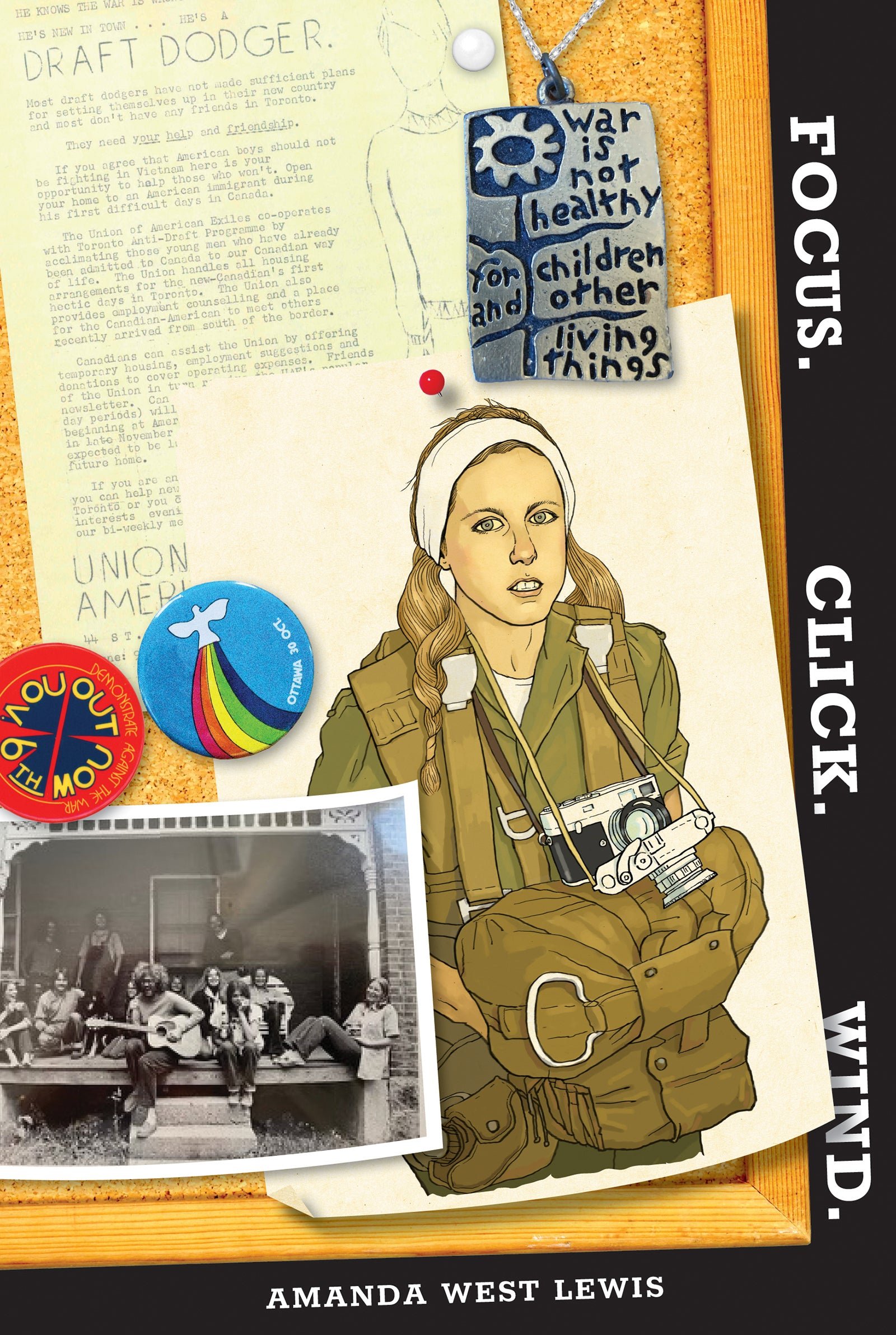

Guest Post: Amanda West Lewis on Writing in Three Dimensions

In the kind of synchronicity that feels fake in fiction but is purely wonderful in life, I ended up reading the ARC of Focus. Click. Wind. by Amanda West Lewis right after finishing Dodger Boy by Sarah Ellis. It was wonderful to think about both books in tandem, a middle grade and a YA treatment, both tackling the same period of history and touching on similar themes of war and resistance, social justice and young people finding their own moral ground.

What a turbulent time it was! An American war raged in Vietnam and young American men dodged the draft by crossing the border to Canada.

I asked Amanda if she’d tell me more about the writing of this book. Here’s what she wrote:

Every species passes its cultural knowledge on from one generation to the next. Building on knowledge of the past improves the chance of survival (“Last summer, the best source of food was over there, beyond the next field.”) About ten thousand years ago, humans invented a way to stretch generational knowledge beyond the family and tribe, and beyond living memory. We invented writing. Suddenly we could learn from those outside of our family, our culture, time, and place. We could acquire the wisdom of the ages. And with that wisdom, we could try to make our lives better.

One of the jobs of a writer is to keep knowledge and wisdom alive. As fiction writers, we create characters readers can empathize with. Brain science shows us that empathy –– “the action of understanding, being aware of, being sensitive to and vicariously experiencing the feelings, thoughts and experience of another” (Merriam Webster) –– helps our brains to problem solve. Through fiction, then, we can give our readers a chance to do some empathetic problem solving and thus improve their chances of survival through their understanding of the past.

I was a child of the sixties, fully immersed in the passion and drive of that time. When I was growing up, I was drawn to the stories of young people in the 1930s who were struggling to find political answers to the issues of inequity, injustice, and war that confronted them. The empathy I felt for the youth of the 1930s and 1940s gave me a context for my own reaction to the system that oppressed my 1960s generation. My empathy for the previous generation gave me some ideas for how to move forward.

As a writer, I have access to the past lives I have led. But my writing must live in the present moment. To write for today’s youth, I need to connect with their reality and the crises that pervade their generation. My heart and mind must be constantly weaving their contemporary moment into my knowledge of the past. I must create a Bayeux Tapestry that reflects today through yesterday, while telling a story that leads to tomorrow.

For my novel These Are Not the Words, which takes place in 1963, I created Miranda Billie Taylor by drawing on my own personal history (the warp). Into that story, I wove the contemporary horrors of the opioid crisis (the weft). This makes Missy’s jazz era experiences of her father’s alcoholism and addictions entirely familiar. Her family is shattered, just as so many have been, and she must collect the pieces and build anew, as so many have had to do. The historical context may be different, but the challenges are the same.

Five years later, in Focus. Click. Wind, Missy has renamed herself Billie. It is 1968 and she is completely immersed in the Age of Aquarius. She carries stories from the past in her bones, much as I did. She straddles two eras, from jazz to rock and roll. The warp –– her essential character –– remains the same in both books because it is connected to my own experiences of those years. But the weft of that book’s tapestry is built on the passion, commitment, anger, fierceness, and courage of today’s climate warriors. Extinction Rebellion (weft) nestles into The Weatherman (warp).

The challenge of writing historical fiction is to create the mesh of a tapestry that weaves the generations together. It’s a tapestry of three dimensions –– past, present and future –– one that gives us the opportunity to improve our chance of survival. And maybe, just maybe, as we write we’re giving young people some skills to make the world a better place.

I love what Amanda says here about reflecting today through yesterday, while telling a story that leads to tomorrow. Listen to these lines from the book—that is what they do:

Something we could do.

Feeding chili to southern mommas is not how you start a revolution. But she has a roll of film. Waiting to be developed.”

Here’s a celebration of the young who have to deal with a world they did not make.